The Unexpected Effects of Unpaid Caregiving

The Unexpected Effects of Unpaid Caregiving

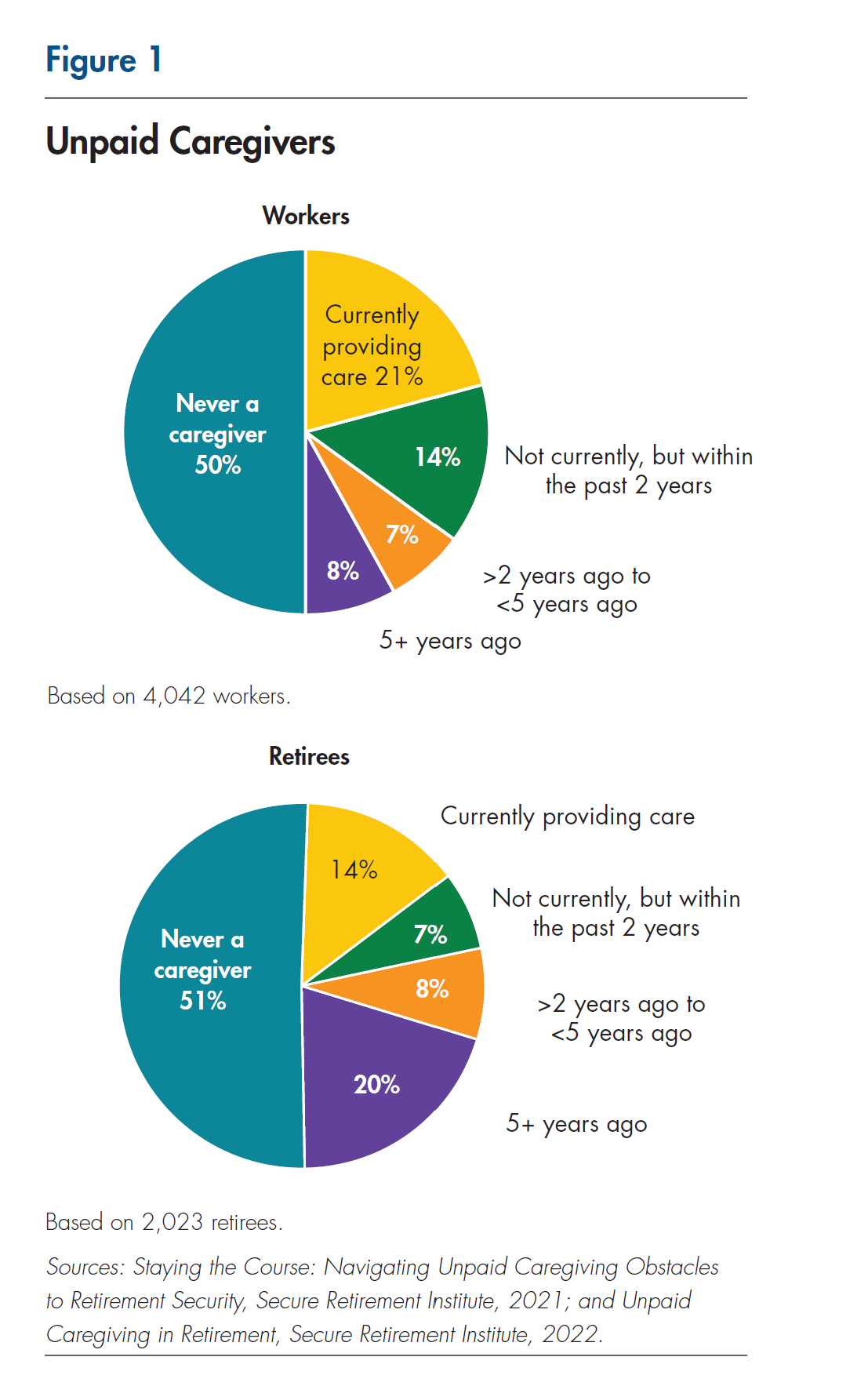

Any type of caregiving can be a financial, physical, and emotional burden for the caregiver. Unpaid caregiving — helping someone on a regular basis with personal needs, household chores, managing finances, arranging for outside services, or running errands — can have profound and lasting effects. Recent LIMRA research finds that 1 in 5 workers and 14 percent of retirees are currently unpaid caregivers (Figure 1). In addition, 42 percent of workers and 30 percent of retirees engaged in this type of caregiving in the past four years. Who are these caregivers, how does caregiving affect worker retirement savings, and how can workplace benefits and retirement planning help?

Helping unpaid caregivers manage competing demands on their time and energy and avoid negative financial impacts should be an important consideration not only for employers, but also for the retirement industry. Understanding the characteristics of workers and retirees who provide unpaid care to others allows for a better understanding of the market, more targeted messaging, and specific planning activities.

Almost half of workers who have been unpaid caregivers (48 percent) experience an impact at work due to unpaid caregiving. Reducing hours and taking unpaid leave are the most common; nearly 1 in 10 gave up on work entirely (but didn’t retire) or turned down a promotion as a result of unpaid caregiving demands. Younger generations of workers are more likely to have experienced at least one impact (60 percent of Gen Z/Millennials and 40 percent of Gen X versus 29 percent of Baby Boomers). In addition, 6 in 10 workers who have been unpaid caregivers experience a negative financial result. The most common financial impacts of unpaid caregiving include taking on additional debt (21 percent), using up emergency savings (21 percent), and ceasing to save for emergencies (17 percent). Although negative financial impacts specific to retirement accounts are less common than increased debt and decreased emergency savings, any negative financial effect may reduce long-term retirement savings because workers often operate under hierarchies of financial needs. For instance, they may be less likely to save for retirement if they do not have an emergency savings account to cover short-term financial needs. Providing unpaid care can also put workers at risk for an early retirement. For retirees, the effects of unpaid caregiving may be more emotional and physical than financial. Nearly half (45 percent) of retirees who are current unpaid caregivers feel that they spend too much time on caregiving.

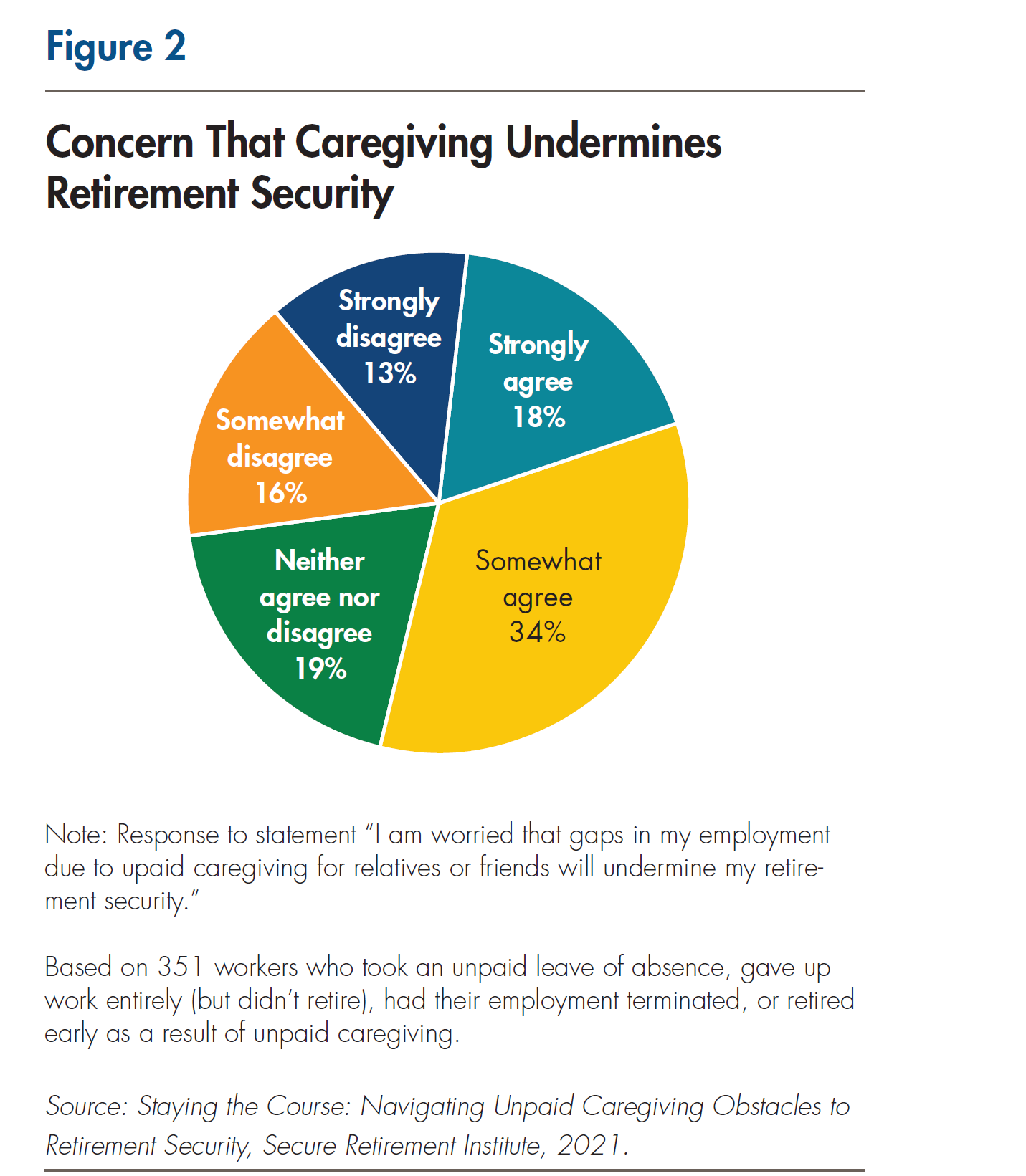

Half of caregivers who have interrupted their employment to provide unpaid care are worried about the impact work disruptions may have on their retirement security (Figure 2). Unpaid caregiving and the potential gaps in employment that result from it are part of life, but they do not have to come at the cost of retirement security.

Secure Retirement Institute® (SRI®) research finds that workplace plans can play an important role in sustaining savings through informal and formal catch-up activities, as well as timely outreach, education, and communication to participants. Furthermore, the impact of unpaid caregiving on workers varies in intensity, duration, and timing, which necessitates flexibility in their benefits. Workers who give care need flexible benefits — in terms of time and place of work, as well as paid time off. In addition, these benefits can help workers continue to save for retirement by maintaining income.

Workplace emergency saving accounts, in conjunction with retirement savings, may help build workers’ safety nets back up and help them obtain both their short- and longterm financial security. Over 60 percent of unpaid caregivers with benefits (such as onsite childcare, caregiving support groups, information, referrals, and counseling to help caregivers) feel that their employers support their caregiving challenges, compared with less than a quarter of those without available caregiving benefits. Unpaid caregiving can present a great challenge for workers, but support from employers can make a difference.

Among the 12 percent of working former caregivers who reduced their hours at work, took a leave of absence, or otherwise interrupted their employment in order to provide regular care to a relative, nearly 7 in 10 took steps to compensate for savings lost due to caregiving employment gaps. Increasing their workplace retirement savings rate after the gap in employment was the most common action, with 39 percent doing so. Compared with 2016, women currently are more likely to take action to compensate for lost retirement savings due to unpaid caregiving leave. However, women also are less likely than men are to compensate for lost retirement savings resulting from caregiving employment gaps.

Among those who experienced an employment gap due to unpaid caregiving, 55 percent of women took action to compensate for lost retirement savings due to this leave, compared to 86 percent of men. Gaps in employment for unpaid caregiving often result in lost retirement savings, especially for women who are less likely to take steps to compensate. As employees return to the workforce postpandemic, taking steps to boost savings — such as ensuring they contribute to meet the employer match, increase savings rates, or make catch-up contributions if permitted — can help improve retirement preparedness. Workplace benefits and retirement planning should take into account the very real possibility that workers and even retirees may need to provide unpaid caregiving for someone. Supporting caregivers at the workplace and with intentional planning can ease the burden for workers and, ultimately, retirees. Planning for unpaid caregiving can mean the difference between a secure financial future and one of uncertainty.